Today we leave our awesome lodging and the national park, and need to return the rental car back to Kagoshima. It's a short 1 hour drive back, so there's plenty of time to use a car to take in sights which would've been not easy or impossible to do by public transportation.

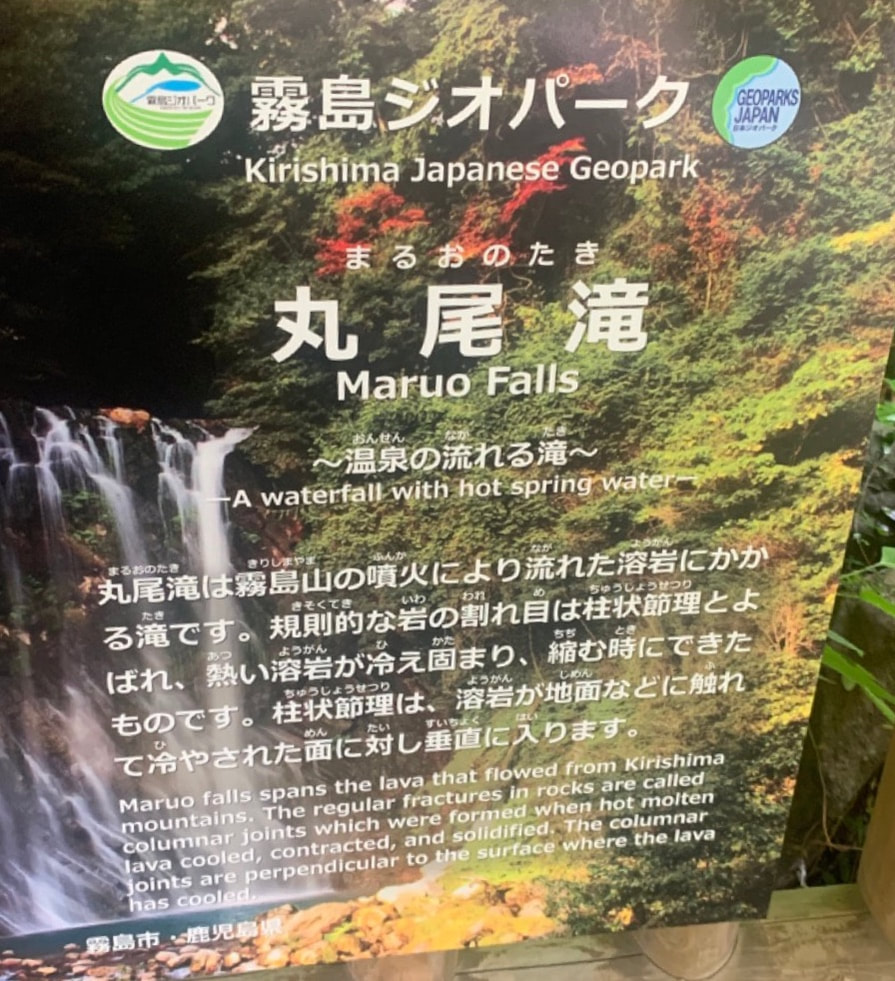

First up is Maruo Falls, just outside of town.

First up is Maruo Falls, just outside of town.

Our rental sits at the ready (the one on the right)...

A random sighting of a Japanese orbital rocket seen along the way (Japan's launch base is just south of us, on the island next to the one we'll ferry across to tomorrow)...

We're now driving down into the extreme southwest corner of this island of Kyushu - onto the peninsula of Satsuma.

There's what they call "Little Mount Fuji".

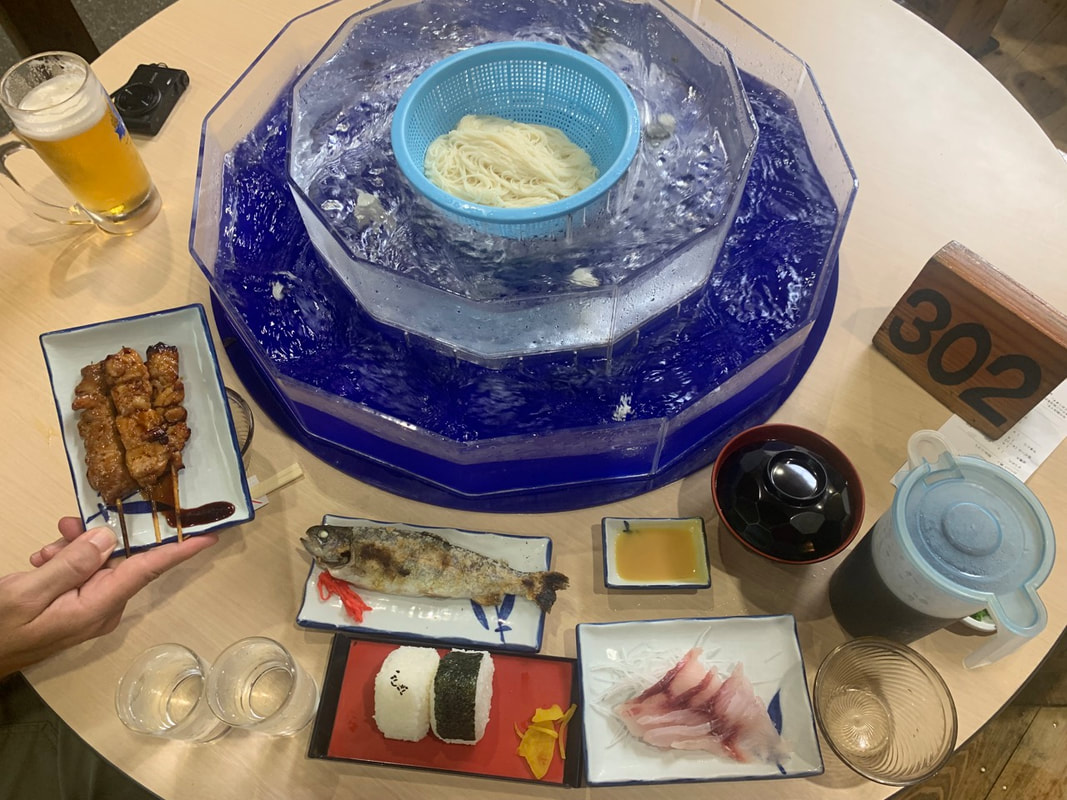

Gerri says we should eat here - a uniquely curious thing is going on...

...that starts with a hike down into the holler...

....and ends with rice noodles being put into some sort of washing machine looking thingie.

Here's a real stamp steel sheet beauty of an automobile.

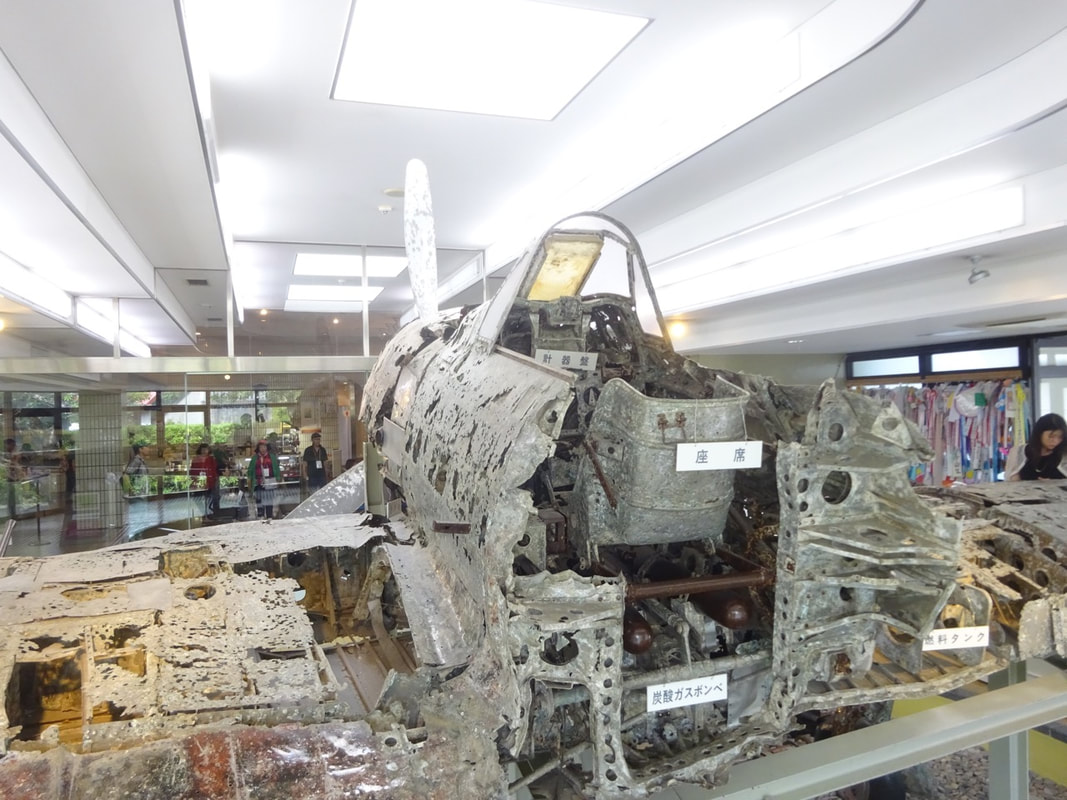

And now we finish the day with a tour of Japan's national memorial museum to World War II's kamikaze mission.

The airbase at Chiran, Minamikyūshū, on the Satsuma Peninsula served as the departure point for hundreds of Special Attack or kamikaze sorties launched in the final months of World War II - especially the Battle for Okinawa. A peace museum dedicated to the pilots, the Chiran Peace Museum for Kamikaze Pilots now marks the site.

"Kamikaze, officially Shinpū Tokubetsu Kōgekitai ("Divine Wind Special Attack Unit"), were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units of military aviators who flew suicide attacks against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of World War II, intending to destroy warships more effectively than with conventional air attacks. About 3,800 kamikaze pilots died during the war, and more than 7,000 allied naval personnel were killed by kamikaze attacks. Kamikaze aircraft were essentially pilot-guided explosive missiles, purpose-built or converted from conventional aircraft. Pilots would attempt to crash their aircraft into enemy ships in what was called a "body attack" (tai-atari) in aircraft loaded with bombs, torpedoes, and/or other explosives. About 20% of kamikaze attacks were successful. The Japanese considered the goal of damaging or sinking large numbers of Allied ships to be a just reason for suicide attacks; kamikaze was more accurate than conventional attacks, and often caused more damage. Some kamikazes were still able to hit their targets even after their aircraft had been crippled by anti-aircraft guns.

The attacks began in October 1944, at a time when the war was looking increasingly bleak for the Japanese. They had lost several important battles, many of their best pilots had been killed, their aircraft were becoming outdated, and they had lost command of the air. Japan was losing pilots faster than it could train their replacements, and the nation's industrial capacity was dramatically diminishing relative to that of the Allies. These factors, along with Japan's unwillingness to surrender, led to the use of kamikaze tactics as Allied forces advanced towards the Japanese home islands.

The tradition of death instead of defeat, capture, and shame was deeply entrenched in Japanese military culture; one of the primary values in the samurai life and the Bushido code was loyalty and honor until death. In addition to kamikazes, the Japanese military also used or made plans for non-aerial Japanese Special Attack Units, including those involving Kairyu (submarines), Kaiten (human torpedoes), Shinyo (speedboats), and Fukuryu (divers)."

Historians say this effort was foolhardy from its conception, and would never have resulted in a turn of tide in the war, even without the atomic bombings. These many young men were convinced to join this effort, presumably without the full knowledge that their leadership possessed about the ultimate futility of this campaign.

The airbase at Chiran, Minamikyūshū, on the Satsuma Peninsula served as the departure point for hundreds of Special Attack or kamikaze sorties launched in the final months of World War II - especially the Battle for Okinawa. A peace museum dedicated to the pilots, the Chiran Peace Museum for Kamikaze Pilots now marks the site.

"Kamikaze, officially Shinpū Tokubetsu Kōgekitai ("Divine Wind Special Attack Unit"), were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units of military aviators who flew suicide attacks against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of World War II, intending to destroy warships more effectively than with conventional air attacks. About 3,800 kamikaze pilots died during the war, and more than 7,000 allied naval personnel were killed by kamikaze attacks. Kamikaze aircraft were essentially pilot-guided explosive missiles, purpose-built or converted from conventional aircraft. Pilots would attempt to crash their aircraft into enemy ships in what was called a "body attack" (tai-atari) in aircraft loaded with bombs, torpedoes, and/or other explosives. About 20% of kamikaze attacks were successful. The Japanese considered the goal of damaging or sinking large numbers of Allied ships to be a just reason for suicide attacks; kamikaze was more accurate than conventional attacks, and often caused more damage. Some kamikazes were still able to hit their targets even after their aircraft had been crippled by anti-aircraft guns.

The attacks began in October 1944, at a time when the war was looking increasingly bleak for the Japanese. They had lost several important battles, many of their best pilots had been killed, their aircraft were becoming outdated, and they had lost command of the air. Japan was losing pilots faster than it could train their replacements, and the nation's industrial capacity was dramatically diminishing relative to that of the Allies. These factors, along with Japan's unwillingness to surrender, led to the use of kamikaze tactics as Allied forces advanced towards the Japanese home islands.

The tradition of death instead of defeat, capture, and shame was deeply entrenched in Japanese military culture; one of the primary values in the samurai life and the Bushido code was loyalty and honor until death. In addition to kamikazes, the Japanese military also used or made plans for non-aerial Japanese Special Attack Units, including those involving Kairyu (submarines), Kaiten (human torpedoes), Shinyo (speedboats), and Fukuryu (divers)."

Historians say this effort was foolhardy from its conception, and would never have resulted in a turn of tide in the war, even without the atomic bombings. These many young men were convinced to join this effort, presumably without the full knowledge that their leadership possessed about the ultimate futility of this campaign.

| USS Bismarck Sea (CVE-95) served in support of the landings on Iwo Jima. On 21 February 1945, she sank off of Iwo Jima from two kamikaze attacks, killing 318 crewmen. She was the last aircraft carrier in U.S. service to sink due to enemy action. | Tim's father's brother was a sailor on the USS Bismarck Sea and one of the sailors lost. This kamikaze mission originated from outside of Tokyo. |

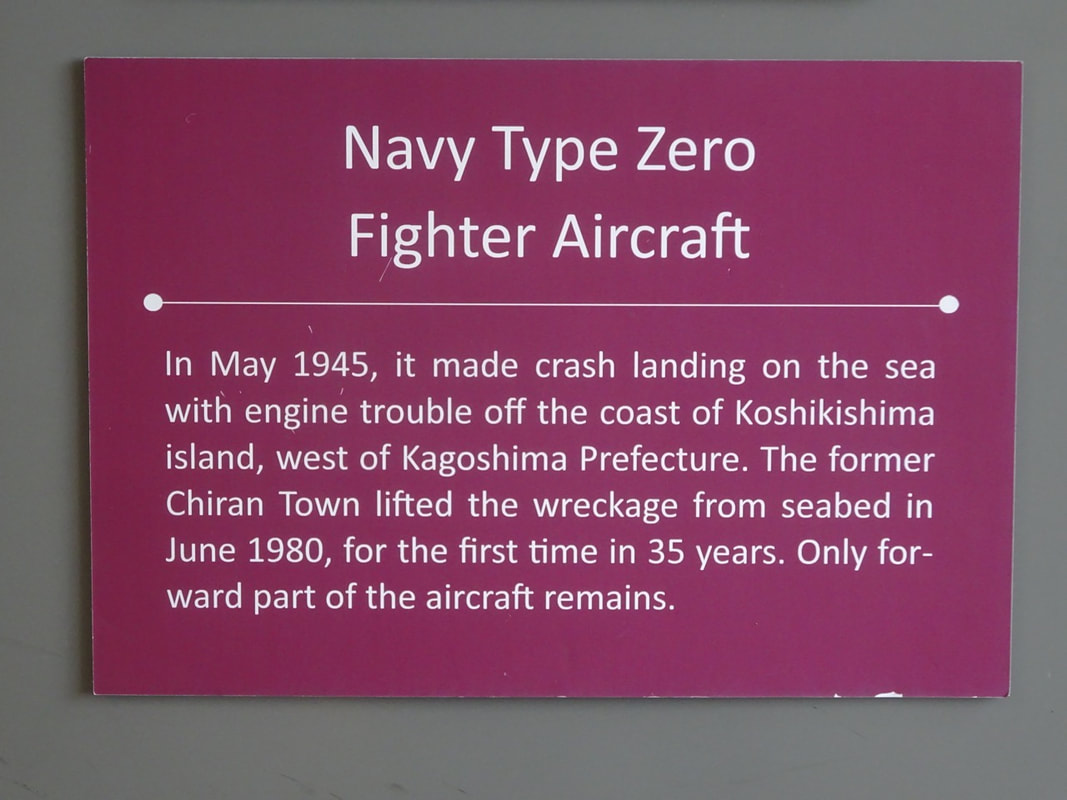

An aircraft on display outside the museum and typical of those used in kamikaze attacks.

No photos were permitted within the majority of the museum - there were photos posted of just about every member who flew to their deaths, and a large collection of mementos donated by their families.

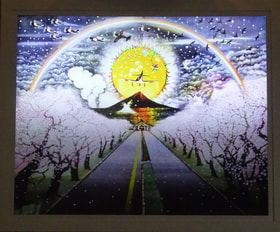

These next two photos are from a train station poster promoting the museum (we snapped photos right off the poster):

Re-created pilot's quarters used during the last few days before their missions.

On departure from the museum grounds, young boys are seen heading home from their school activities.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed